A Day in the Life: Gorilla Doctor

When Dr. Gaspard Nzayisenga thought about a career in veterinary medicine, he never imagined he would one day become a gorilla doctor—a veterinarian caring for endangered wild mountain gorillas in Rwanda.

“Every single day that I am out in the forest with the gorillas I realize that when we save gorillas, we are also saving ourselves,” he said.

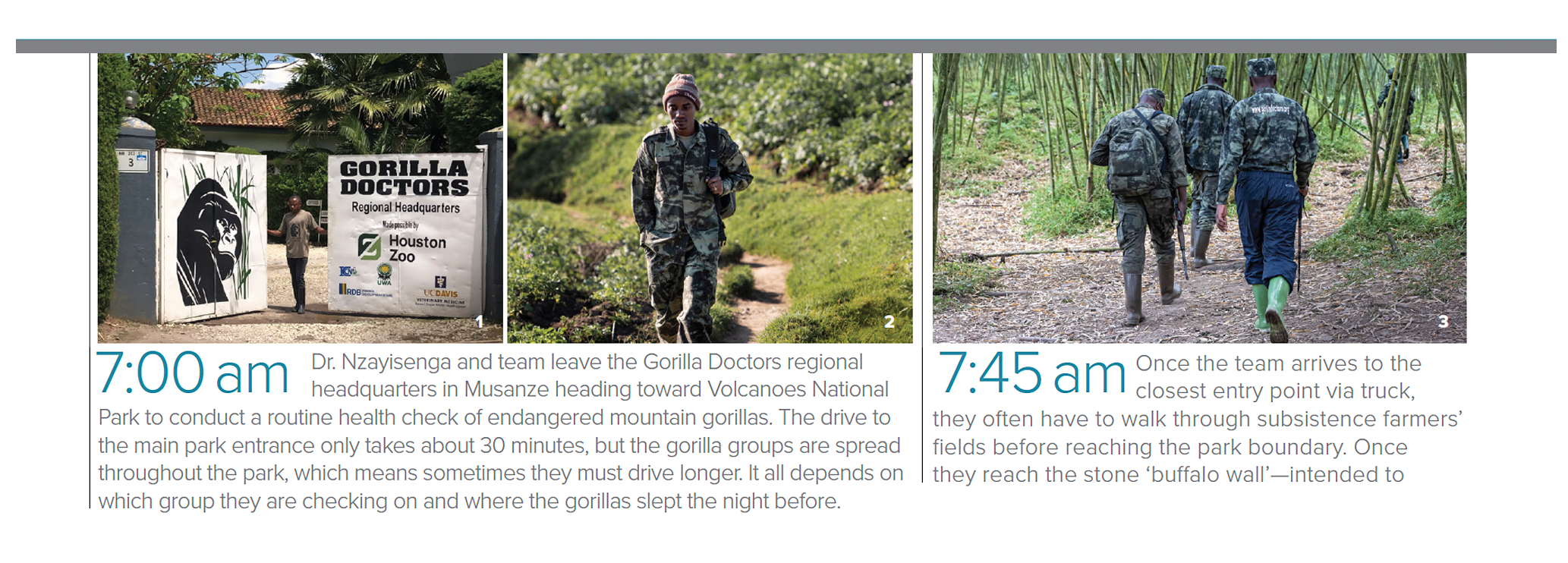

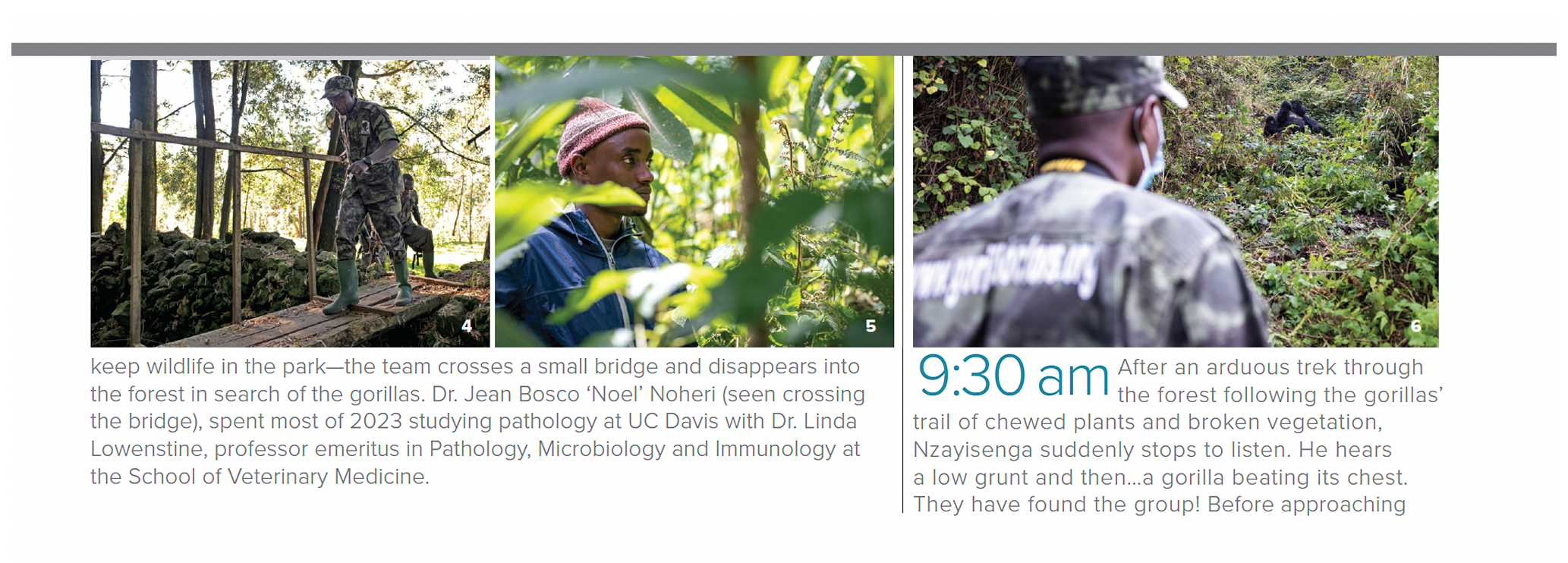

This understanding has guided Nzayisenga from his early days with Gorilla Doctors as an intern in 2014. Gorilla Doctors is a partnership of the school’s Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center, and the nonprofit Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project (MGVP, Inc.), which began at the request of Dian Fossey, the famed primatologist who dedicated her life to the study and conservation of mountain gorillas.

In the early 1980s, mountain gorillas were on the brink of extinction; many were dying unnecessarily from snare injuries and infected wounds. Fossey knew veterinary care could make a difference for their long-term survival. The first American “gorilla doctor” arrived in Rwanda in 1986. Today, Nzayisenga is one of twelve African veterinarians working across Rwanda, Uganda, and Democratic Republic of Congo to provide life-saving veterinary care to both mountain and eastern lowland, or Grauer’s gorillas.

There are always surprises when you work with a wild animal in their forest environment.”

“There are always surprises when you work with a wild animal in their forest environment. When an individual gorilla is ill or injured, we perform interventions to provide treatment—never removing our ‘patient’ from the forest and always working while surrounded by their gorilla family,” said Nzayisenga.

As it turns out, the patient doesn't always stay surrounded by the gorilla family. Nzayisenga recalled an intervention early in his career to rescue an infant mountain gorilla that had been caught in a snare. The wire was wrapped tightly around her arm, threatening serious injury. →

Article continues after images.

I am humbled to play a small role in helping to preserve this extraordinary species for future generations.”

“The gorilla group was a challenging one. It had many silverbacks (adult male gorillas who protect the group) and was large in size,” Nzayisenga recalled. “We successfully darted the infant with anesthesia but then the entire group ran away leaving the infant behind! We worked quickly to remove the snare and treat her wounds but as the group was moving very quickly through dense vegetation and steep terrain, we had to race to get the infant back with her group.” “It was a long day and it was growing dark, but when I saw the infant reunited with her mother it was a great moment. We were all so relieved and today that infant is now a young adult who will soon become a mother herself.”

Seeing individual gorillas grow and thrive over their lifetimes has been one of the most rewarding aspects for Nzayisenga. For most of his life, mountain gorillas have been classified as “critically endangered.” In 2018, their conservation status changed to “endangered” and mountain gorillas are the only great ape in the wild whose numbers are increasing. Research has shown that up to 40% of the habituated mountain gorilla annual population growth rate is the direct result of Gorilla Doctors’ life-saving veterinary care.

“This is a big win for wildlife, for conservation and for my country. Rwanda and Rwandans understand the intrinsic value of mountain gorillas to our shared global community and, as a father, I am humbled to play a small role in helping to preserve this extraordinary species for future generations.”

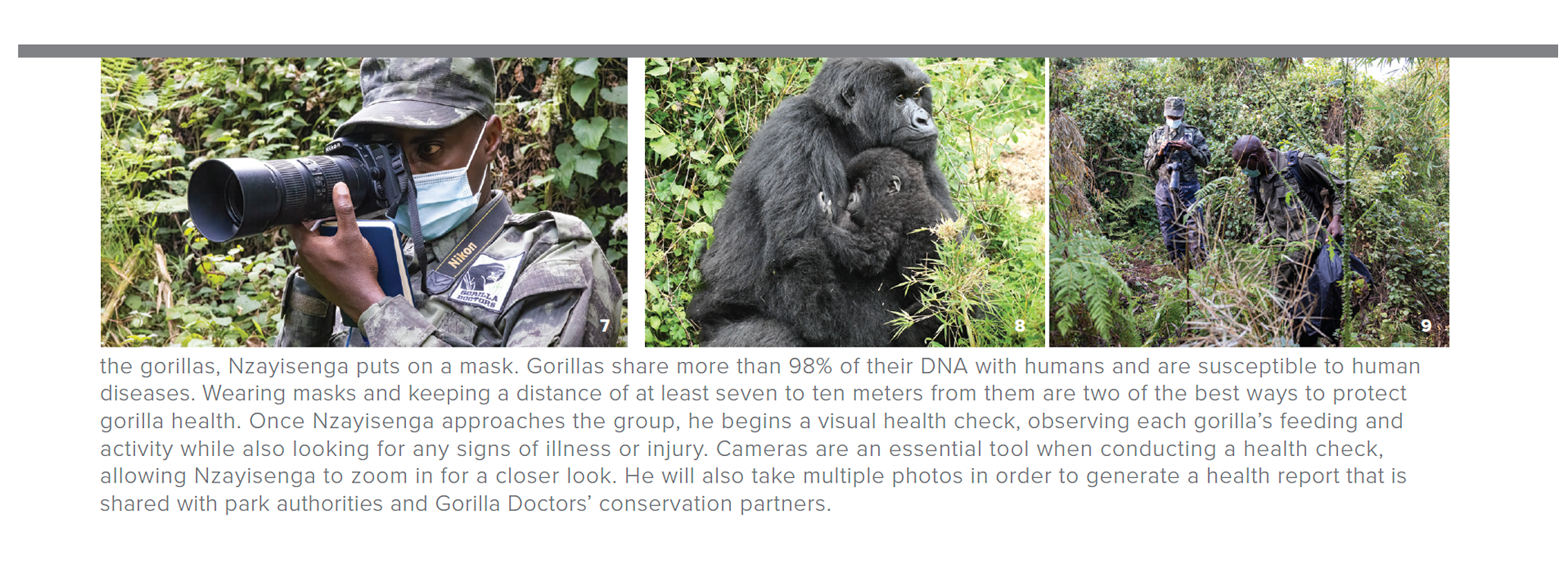

That said, there is still work to be done and the future of mountain gorillas is not secure. Just over 1,000 mountain gorillas remain on the planet. Existing threats to gorillas have intensified and novel threats are emerging. Gorillas and humans share more than 98% of their DNA, making gorillas susceptible to human diseases (and vice versa). Advances in human medicine have the potential to transform great ape medicine and Gorilla Doctors’ scientific research is working to adapt the latest technologies to address the greatest health threats to eastern gorillas.

There is so much work to be done, so much of our natural world to protect and care for.”

“There is so much work to be done, so much of our natural world to protect and care for. If you want to be a wildlife veterinarian, find every opportunity you can to get involved,” Nzayisenga said. “Volunteer. Spend time out in nature. Read. Learn from experts in the field. But most of all, learn from the animals themselves. They are our greatest teachers.”

Timeline photo credits: Skyler Bishop for Gorilla Doctors: 2, 3, 4, 9; Will Wilson for Gorilla Doctors: 5, 6, 7, 10, 12; Gorilla Doctors: 1, 8, 11.